The 1841 Preemption Act used by Jane Ferris was passed by Congress in response to the demands of the Western states that squatters be allowed to preempt lands. Immigrants who were residing and developing the land often settled on public lands before they could be surveyed and auctioned by the U.S. government prior to the 1869 federal survey. At first the squatter claims were not recognized, but in 1830 Congress passed the first of a series of temporary preemption laws. Opposition to preemption came from Eastern states, which saw any encouragement of western migration as a threat to their labor supply.

A permanent preemption act was passed only after the Eastern states had been placated by the principle of distribution, where the proceeds of the government land sales would be distributed among the states according to population, a remedy which clearly favored the East. Distribution was discarded in 1842, but preemption survived. The act of 1841 permitted settlers to stake a claim of 160 acres and after a year of residence to purchase it from the government for as little as $1.25 an acre before it was offered for public sale.

After the passage of the 1862 Homestead Act, the value of preemption for bona fide settlers declined, and the practice more and more became a tool for speculators. Generally, the use of preemption to acquire property was fairly common in the late-nineteenth century in the Sheridan, Montana area. As the mineral wealth of Alder Gulch played out during the late 1860s and into the 1870s, some miners were naturally inclined to attempt new forms of economic viability. However, official General Land Office surveys of the Ruby Valley were not complete, prompting significant local individuals to use preemption to secure 160 acres of land. Overall, approximately fifty farmsteads were established in the Sheridan region using preemption during the 1870s. By the 1880s, this number fell dramatically to approximately twelve such applications, some of which were cancelled. By this time, surveys of Montana were complete and use of the 1862 Homestead Act as well as cash sales was much more common. Congress repealed the Preemption Act in 1891.

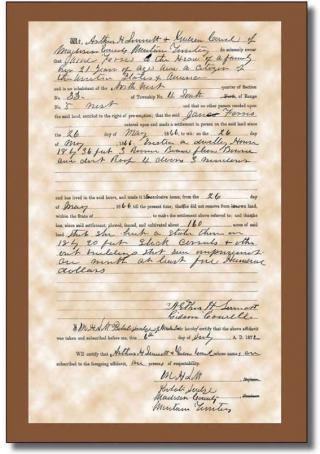

Locally in the Ruby Valley what was quite uncommon was the use of preemption by a woman. Jane Ferris appears to be the only woman in Sheridan-area history to use preemption to secure land during the formative decades of the 1870s and 1880s. At that time, Ferris’ property was apparently part of a larger property owned by John Barber, who had claimed the land in 1864. According to local history, Jane Ferris worked as a housekeeper for John until he died in 1872. In July 1872, using the 1841 Preemption Act, Jane Ferris sought to patent the 160 acres. In the application, Ferris stated that she had resided on the land since May 1866. Unfortunately, Jane Ferris was unable to enjoy her home for very long. She died in 1873 leaving her two children orphans. Her experience is clearly an important one that demonstrates the role of women in the American West as heads of households. How they came west, claimed land, and took on the role as a head of household and sole family provider.

A German immigrant, Fred Hermsmeyer, purchased the historic ranch in 1883. He had arrived in Alder Gulch in 1866. Fred came as part of the gold rush and began working various claims. Over the next decade he made an estimated $80,000, and parlayed his earnings into various real estate ventures and investments. In 1870, he returned to Cincinnati and married Minnie Willmire, returning to Alder Gulch that same year. He continued mining until 1877, when he purchased a sawmill six miles east of Sheridan. It was in 1883, during his years as a sawmill owner, that he purchased the historic ranch.

A German immigrant, Fred Hermsmeyer, purchased the historic ranch in 1883. He had arrived in Alder Gulch in 1866. Fred came as part of the gold rush and began working various claims. Over the next decade he made an estimated $80,000, and parlayed his earnings into various real estate ventures and investments. In 1870, he returned to Cincinnati and married Minnie Willmire, returning to Alder Gulch that same year. He continued mining until 1877, when he purchased a sawmill six miles east of Sheridan. It was in 1883, during his years as a sawmill owner, that he purchased the historic ranch.

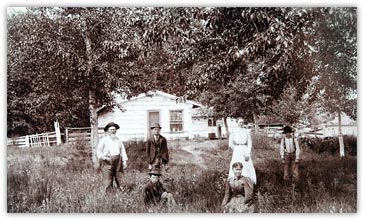

After settling there, Fred, his wife, Minnie, and their family of six children were joined by a nephew, George Hermsmeyer, his wife, Anna, and their daughter. By the mid-1880s, Fred Hermsmeyer had moved his family to Sheridan, leaving the nephew, George, and his family on the homestead. George died in 1917, and the following year, his wife Anna remarried and moved from the homestead.

six children were joined by a nephew, George Hermsmeyer, his wife, Anna, and their daughter. By the mid-1880s, Fred Hermsmeyer had moved his family to Sheridan, leaving the nephew, George, and his family on the homestead. George died in 1917, and the following year, his wife Anna remarried and moved from the homestead.

This picture was taken in 1898 of the George Hermsmeyer family.

In the background is the 1866 original cabin.

It was during the Hermsmeyer era of ownership, from 1883 to 1917 that the historic property began to take the shape that is still expressed today. The original Ferris-era log cabin was built in 1866. It was 18′ x 36′ of 8″ unpeeled pine logs. Jane Ferris noted on her preemption application that the original cabin had three rooms, a board floor, a board and dirt roof, four doors and three windows. The log portion of the sheep barn was built in 1866 at the same time as this original log cabin.

It was during the Hermsmeyer era of ownership, from 1883 to 1917 that the historic property began to take the shape that is still expressed today. The original Ferris-era log cabin was built in 1866. It was 18′ x 36′ of 8″ unpeeled pine logs. Jane Ferris noted on her preemption application that the original cabin had three rooms, a board floor, a board and dirt roof, four doors and three windows. The log portion of the sheep barn was built in 1866 at the same time as this original log cabin.

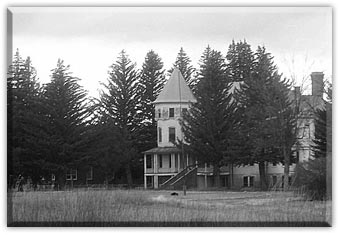

In 1900, Fred and George Hermsmeyer remodeled the original cabin and reduced it to 18′ x 20′. This is the present day kitchen – dining room. They added a large two-story residential addition to the log cabin. Fred and George designed the interior as well as the exterior walls with a unique heating and cooling system . . . the entire height  of the upstairs and downstairs walls have red mortared bricks between the studs.

of the upstairs and downstairs walls have red mortared bricks between the studs.

Other buildings and structures built by Fred and George Hermsmeyer include the log bunkhouse northeast of the main residence, the substantial root cellar, the blacksmith shop and the horse barn. During the Fred Hermsmeyer era on the historic homestead, his two daughters asked their father for some space of their own. He built them the 12′ x 18′ log bunkhouse. It is built out of cottonwood logs and sits close to the original cabin.

For the next several years, the ownership of the property is somewhat unclear, with shifting ownership that is reflective of the deteriorating agricultural and economic conditions throughout the West in the 1920s and 1930s. County records show that the property passed among several individuals until William Bray took ownership in 1927, then again in 1932. In December 1932, Bray apparently defaulted on a $12,000 mortgage, and the Vermont Loan and Trust foreclosed. In May 1934, the Monaduock Savings Bank took possession of the mortgage.

For the next several years, the ownership of the property is somewhat unclear, with shifting ownership that is reflective of the deteriorating agricultural and economic conditions throughout the West in the 1920s and 1930s. County records show that the property passed among several individuals until William Bray took ownership in 1927, then again in 1932. In December 1932, Bray apparently defaulted on a $12,000 mortgage, and the Vermont Loan and Trust foreclosed. In May 1934, the Monaduock Savings Bank took possession of the mortgage.

On June 11, 1937, Stanley and Helen Fenton purchased the ranch from the bank for $3,250. The family spent the summer of 1937 repairing the home so Helen’s parents could move in before winter.  The following spring, Stanley, Helen and their two children joined the elderly couple on the homestead. Stanley and Helen worked side by side until Stanley’s unfortunate death in 1959. The following year, Helen sold 130 acres to her son and daughter-in-law, keeping the 30 acres where her home and the buildings were. She lived there until her death in November, 2000 at the age of 98. She had lived there for 63 years.

The following spring, Stanley, Helen and their two children joined the elderly couple on the homestead. Stanley and Helen worked side by side until Stanley’s unfortunate death in 1959. The following year, Helen sold 130 acres to her son and daughter-in-law, keeping the 30 acres where her home and the buildings were. She lived there until her death in November, 2000 at the age of 98. She had lived there for 63 years.

When Stanley and Helen Fenton moved to the homestead in 1937, they made the decision that the thirteen acres across the creek from the house would be left untouched. The family has always honored that and today it is home to wildlife and many kinds of birds. Helen documented more than 80 different species of birds she had seen on the property throughout the years. We welcome visitors to explore the entire 30 acres of property.

In 1943, Stanley and Helen Fenton became involved with the state orphanage located 9 miles away in Twin Bridges. They felt that the one thing they could do for these underprivileged children was to give birthday parties in a home setting. Any child who was over six and had a birthday the previous month was invited to the birthday party. The parties were held in private homes throughout the community with the majority of the parties being at Helen and Stanley’s home. The children would spend the day exploring the property and being a part of the ranching activity for a day. For their first party, Helen and Stanley purchased furniture to give the children a feeling of a home. The living room’s focus is still those original pieces of furniture purchased for the children from the state orphanage.

In 1943, Stanley and Helen Fenton became involved with the state orphanage located 9 miles away in Twin Bridges. They felt that the one thing they could do for these underprivileged children was to give birthday parties in a home setting. Any child who was over six and had a birthday the previous month was invited to the birthday party. The parties were held in private homes throughout the community with the majority of the parties being at Helen and Stanley’s home. The children would spend the day exploring the property and being a part of the ranching activity for a day. For their first party, Helen and Stanley purchased furniture to give the children a feeling of a home. The living room’s focus is still those original pieces of furniture purchased for the children from the state orphanage.

The original historic 160 acres continues to be a part of the present working family ranch. The outside buildings and surrounding yard still display the tools, saddles, harnesses and equipment used in the early years of ranching. The log bunkhouse built for Fred Hermsmeyer’s daughters was used as an ice house from 1937 until 1946 when electricity was first introduced to the ranch. So much of the history we have on the original 160 acres is due to the fact that Fred’s two daughters came to see Stanley and Helen in the 1950s and shared their memories.

The original historic 160 acres continues to be a part of the present working family ranch. The outside buildings and surrounding yard still display the tools, saddles, harnesses and equipment used in the early years of ranching. The log bunkhouse built for Fred Hermsmeyer’s daughters was used as an ice house from 1937 until 1946 when electricity was first introduced to the ranch. So much of the history we have on the original 160 acres is due to the fact that Fred’s two daughters came to see Stanley and Helen in the 1950s and shared their memories.